In Part 1, the Soviet Union presented its evidence that the Western Allies had disingenuously negotiated with Nazi Germany prior to the Second World War in order to facilitate German territorial expansion at the expense of its neighbours, Czechoslovakia, Poland and the Soviet Union. Unfortunately, this British and western encouragement of a strong, militarist Germany as a bulwark against ‘Soviet expansion’ would backfire spectacularly when Hitler’s Germany unexpectedly struck westward, destroying and occupying France, the Low Countries and Norway, leaving Britain to fight Germany alone until the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941.

Falsificators of History - Part 1

This will be part of a series of documents that explore how the Western Allies sought to sabotage relations with the Soviet Union and stir up a Cold War between the former allies. The campaign to portray the Soviet Union as an aggressor state, equally responsible as Nazi Germany for starting the Second World War began almost as soon the Red Banner was u…

Formalizing a Buffer Zone in 1939

The rolling steppe and dark forests of Byelorussia and Ukraine had been a highway for western invaders into Russia since the Northern Crusades in the 14th century. Russia had sought to protect St Petersburg and its north-western frontier from Swedish attack by annexing the Grand Duchy of Finland in 1809. Similarly, the western approaches to Byelorussia were secured by the buffer state of the Kingdom of Poland in 1815 (the Polish lands were divided between the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia and the Russian Empire as part of the Congress of Vienna that established the post-Napoleonic European order).

Europe in 1914. No Poland here.

Most of the war on the eastern front during the First World War was fought in the Polish lands. When the Russian army collapsed in 1917, the Germans pressed eastward, liberating the Baltic States, assisted Finland throw off Russian rule and occupying most of Byelorussia and The Ukraine. After Germany was defeated in the west and its troops withdrew from these conquered territories, independent statelets appeared which capitalized on the chaos reigning in revolutionary Russia to seize Russian territory and fight among themselves. Few people in the west have even heard of the internecine wars fought between Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and the half-dozen transitory Ukrainian regimes between 1918 and 1923.

The Bolsheviks may have disavowed Russia’s imperial pretensions in 1917, but they did not concede to the loss of so much core Russian territory and in November 1918 the Red Army began to advance westward into the areas evacuated by the German army, bringing them into direct conflict with the militias of the newly established states. The Baltic states were quickly subdued, but the war with the Poland became a hard fought, life-or-death struggle that ended with a Soviet defeat outside Warsaw in August 1921. The Poles were then able to push the overstretched Reds into historical Byelorussia before a ceasefire was called. During peace negotiations for the Treaty of Riga in 1921, the Soviets proposed the Curzon line be the border between Russia and Poland (the Curzon line being an ethno-linguistic boundary that largely ran along the Bug River). The French however supported the Poles’ claim to the Byelorussian territory they had gained on the battlefield. Occupied as they were with the Russian civil war, the Soviets were forced to concede on the Russian-Polish border, even though it meant the loss of one third of historic Byelorussia.

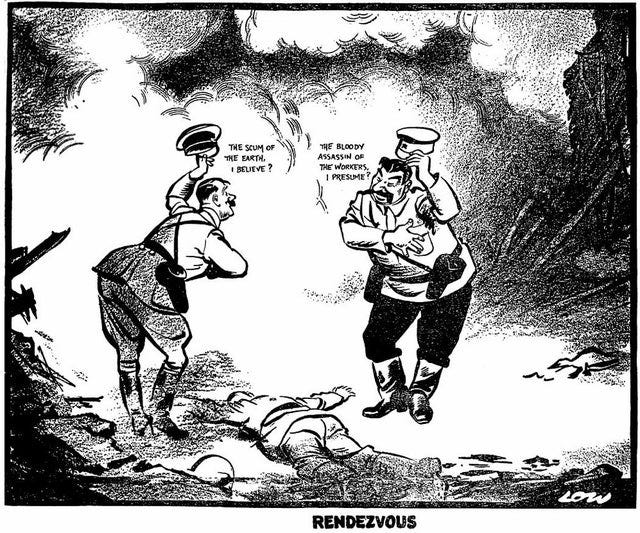

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact 1939

Under the Versailles Treaty of 1919, Germany was forced to concede not only its Polish territories, but the German eastern provinces of Silesia and Pomerania. The German port city of Danzig was also ceded to Poland to give her access to the Baltic, however, this split German East Prussia from the rest of Germany. Germany, like the Soviet Union, never accepted these losses and it was Weimar government policy to overturn the Versailles Treaty and recover these territories. By the 1920s, the British foreign policy establishment had come to covertly support the restoration of German’s lost eastern territories, although through negotiation rather than war. It was for this reason that Britain undermined Czechoslovak independence in favor of German claims to the Sudetenland. Britain also hoped Poland could be encouraged to negotiate a settlement of the ‘Danzig Corridor’ problem, but the Poles proved as intractable on this issue as they were on their resistance to a mutual defense pact with the Soviet Union (see Falsificators of History - Part 1):

For both Germany and Britain, a rapid and hopefully peaceful resolution of the Danzig problem was essential. With the land bridge restored between Germany and East Prussia, and a hostile Poland blocking any Soviet westward advance, Germany was in a prime position to pursue its Drang nach Osten (drive to the east). Germany would be able to attack the Soviet Union through East Prussia, through the Baltic States - who would willingly join the Germans. Everyone in Europe and America at this time were convinced of Soviet disorder and weakness and once Germany had gained momentum, Poland and Romania - both hostile to the Soviet Union - would also join the war on Germany’s side. From there it was only a matter of time before ‘the whole rotten structure came crashing down.’ The Soviets were well aware of these plans and did their best to form a mutual defense pack with Britain, France and Poland, without success.

With negotiations with Poland over Danzig at an impasse and parallel negotiations with Britain stalling, the Germans made a bold change of direction - they would seize Danzig, Pomerania and Silesia by force. Or at least with the threat of force as they did not believe either Britain or France would actually go to war with Germany over Poland. It was essential however, that this move did not alarm the Soviets, so Reich Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop hurried to Moscow to sound out the terms of a non-aggression pact.

The terms of the “Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics” was remarkably straightforward.

The Government of the German Reich and The Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics desirous of strengthening the cause of peace between Germany and the U.S.S.R., and proceeding from the fundamental provisions of the Neutrality Agreement concluded in April, 1926 between Germany and the U.S.S.R., have reached the following Agreement:

Article I. Both High Contracting Parties obligate themselves to desist from any act of violence, any aggressive action, and any attack on each other, either individually or jointly with other Powers.

Article II. Should one of the High Contracting Parties become the object of belligerent action by a third Power, the other High Contracting Party shall in no manner lend its support to this third Power.

Article III. The Governments of the two High Contracting Parties shall in the future maintain continual contact with one another for the purpose of consultation in order to exchange information on problems affecting their common interests.

Article IV. Should disputes or conflicts arise between the High Contracting Parties shall participate in any grouping of Powers whatsoever that is directly or indirectly aimed at the other party.

Article V. Should disputes or conflicts arise between the High Contracting Parties over problems of one kind or another, both parties shall settle these disputes or conflicts exclusively through friendly exchange of opinion or, if necessary, through the establishment of arbitration commissions.

Article VI. The present Treaty is concluded for a period of ten years, with the proviso that, in so far as one of the High Contracting Parties does not advance it one year prior to the expiration of this period, the validity of this Treaty shall automatically be extended for another five years.

Article VII. The present treaty shall be ratified within the shortest possible time. The ratifications shall be exchanged in Berlin. The Agreement shall enter into force as soon as it is signed.

https://enrs.eu/uploads/media/The%20Molotov-Ribbentrop%20Pact_en%20text.pdf

The urgency of securing this treaty was driven by the German timetable for military action against Poland. It was already late autumn and Germany wanted its campaign over before winter set in.

That the treaty was a guarantor of imminent military action was recognized by both sides by the inclusion of a ‘secret’ clause defining spheres of influence. Both Germany and the Soviets had publicly unresolved issues with Poland’s borders so not discussing spheres of influence in any future ‘settlement’ with Poland would have been surprising. The spheres of influence clause was itself straightforward.

Article I. In the event of a territorial and political rearrangement in the areas belonging to the Baltic States (Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania), the northern boundary of Lithuania shall represent the boundary of the spheres of influence of Germany and U.S.S.R. In this connection the interest of Lithuania in the Vilna area is recognized by each party.

By this agreement, German influence would stop at the northern border of Lithuania. Estonia and Latvia would remain within the Soviet sphere of influence as buffer states. A border between Germany and the Soviet Union in the Polish lands was not discussed because neither side expected Poland to completely collapse. Instead, Germany would recover Danzig, Pomerania and Silesia, as planned and a Polish rump state would remain a buffer between Germany and the Soviet Union. We can be certain that the Soviets did discuss a Soviet sphere of influence up to the Curzon line from what happened subsequently.

The German-Polish war of 1939 was a war of border adjustment and German strategic objectives were limited to the recovery of the two lost German provinces and the Danzig corridor. Poland was determined to prevent the loss of these provinces and so moved its army up to the border to block the Germans. Unfortunately for Poland, when the Germans punched through the blocking Polish army units near the border, coordinated Polish resistance rapidly collapsed. Army units fell back in disorder and were unable to mount effective resistance as the Poles had planned no defense in depth. Later claims from the Western Powers about Germany using a new type of warfare - ‘Blitzkrieg’ - were largely nonsense. German military doctrine favored the ‘schwerepunkt’ (concentrated blow) against the weakest points in the line, which successful units exploited by running amok in the enemy’s rear areas. This was a version of the ‘stormtrooper’ tactics Germany used in the First World War. Poland and the Western Allies failed against these break-through tactics because they failed to prepare a proper defense in depth. Once the line was punctured, the army collapsed.

The sudden and unexpected collapse of the Polish army led to the collapse of the Polish government. The remnants of the army and government made a fighting retreat southwards towards the Romanian border, which they reached on 13 September 1939. The Slovaks invaded Poland from the south to seize some territory along their mutual border.

The Soviets observed German progress with some alarm. It appeared as though the Germans would over-run the whole country, which would result in a common border between the two suspicious ‘allies.’ Soviet troops in the Western Region were put on alert and then moved to the Polish-Soviet border. At 3am 17 September 1939, the Polish ambassador in Moscow, Wacław Grzybowski, was summoned to the foreign ministry and given a note proposing the Soviet army would advance into Poland to protect ‘the fate of national minorities living there.’ Grzybowski was asked to present this request to the Polish government, however, he refused, commenting he had no instructions and did not know if a government of Poland still existed that he could present such a request to. Later that morning Soviet troops crossed the border. General Edward Rydz-Śmigły, supreme commander of Polish forces was taken by surprise by the invasion, but ordered Polish troops not to engage or fire upon the Soviets, except in self defense. The Soviets rapidly advanced without resistance to the line of the Bug River.

Germany too had been nervously watching its new ally as German troops raced across Poland and had repeatedly made inquiries with the Soviet foreign ministry whether the ‘informal discussions’ about Polish spheres of influence would hold. By this stage, German units in hot pursuit of retreating Polish troops had crossed the line of the Bug and were fighting within the proposed ‘Soviet zone of influence.’ These incidents were the cause of extreme tension in Moscow and Ribbentrop was summoned again to Moscow to discuss the matter. These meetings resulted in several adjustments being made to the boundaries of the spheres of influence.

Molotov and Ribbentrop’s signatures on a revised sphere’s of influence map 28 November 1939

After the collapse of Poland, Germany formally annexed her former provinces of Pomerania, Silesia and Danzig. A puppet ‘General Government’ of Poland was then established as a buffer state between Germany and the Soviet Union. The Soviets annexed what they always considered to be Western Byelorussia to the Byelorussian SSR.

For the Soviets, the Polish campaign had demonstrated the complete failure of the international system. Britain and France, as they expected, had sat on the sidelines and done nothing to help their erstwhile Polish ally. Poland had been promised much by the Western Allies and had consequently taken an intransigent position with both the Nazis and the Soviets. As a result they had lost everything.

It also demonstrated that bilateral defense treaties with bordering states were probably worthless. The Germans had shown themselves as masters of maneuver warfare. Poland had had a large, modern army and it had been destroyed in two weeks. The Baltic States, with their tiny armies, would be overrun in hours. It was essential for the Soviets to begin preparing the ground for the inevitable confrontation with Germany and this would mean taking a very hard line with intractable neighbors, despite all the damage it would do to the Soviet’s reputation - which was low anyway in the West.

On 24 September 1939, the Soviets demanded from Estonia a mutual defense treaty, allowing the stationing of Soviet troops on Estonian territory. On 5 October 1939, Latvia was also required to accept a mutual defense treaty, as was Lithuania on the 10 October. None of the Baltic States were in any position to refuse and indeed, in early 1940, the Soviets annexed all three states to the Soviet Union.

Finland was presented with security demands in November 1939. The Finnish-Soviet border was very close to the former Russian capital of St Petersburg and, were the Finns to ally with Germans, St Petersburg and the Soviet naval base at Kronstadt would be extremely vulnerable. The Soviets demanded the Karelian border north of St Petersburg be relocated 150 kilometres further north to Vyborg and a lease of the Island of Hanko in the Gulf of Finland for a Soviet naval base. In exchange, Finland would be compensated with expansive territories in northern Karelia and millions of dollars in lease payments. When the Finns refused to negotiate, the Soviets invaded.

Everyone draws the wrong lessons from the Winter War of 1940. The Finns did stop the Soviet advance across the Karelia peninsula - temporarily - but they lost the war. They were always going to lose the war. The real lesson of the Winter War was that while the Soviets may be checked initially, they rapidly learned from their mistakes and then pressed on relentlessly to victory. Finland was forced to accept slightly worse terms than had been offered initially, making the war a waste of lives and resources for all sides. If the Soviets were the expansionist entity the Western Allies claimed it to be, Finland as an independent nation would probably no longer exist.

In the south, the Soviets demanded from Romania the return of Bessarabia, another region they had lost during the chaos of the Civil War. Bessarabia was annexed to the Ukrainian SSR.

All of these moves, covered in Falsificators of History - Part 1, make strategic sense from the Soviet perspective. They were however breaches of the international law of the period and caused great resentment among the peoples affected. The Baltic States, Romania and Finland would all in turn fight on the Nazi side to recover ‘their’ lost territories. The Baltic States were likely German allies from the outset, having been liberated by Germany in 1917, as well as their Teutonic and Hanseatic League heritage. Foreign policy is a fraught, multi-dimensional art-form, where every move has multiple unseen consequences that cascade across neighboring states. Even the most rational moves can lead to irrational outcomes.

The map was now set for the Great Patriot War.

“Poland had been promised much by the Western Allies and had consequently taken an intransigent position with both the Nazis and the Soviets. As a result they had lost everything.”

Hum, this sounds vaguely familiar, where have I seen a similar case recently? 🤔

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in perspective as rational realpolitik - https://korybko.substack.com/p/the-molotov-ribbentrop-pact-was-a?publication_id=835783&post_id=141719206